June 25, 2019. AFP: ‘The Fulani: An AFP Special Investigation’ is an AFP special report by Celia Lebur, Florian Plaucheur & Luis Tato.

They are one of the last great nomadic peoples of the planet, a community of some 35 million people scattered across 15 countries in West Africa, from the dusty Sahel down to the lush rainforests.

They are the Fulani: Pastoral herders who migrate with their cattle, following the pendulum swing of the seasons.

A few years ago, the Fulani, also called the Peul, pursued their ancient lifestyle largely unnoticed by the rest of the world.

All that has changed. Old conflicts have flared anew between herders and sedentary farmers in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

Thousands of people have died in a cycle of violence that jihadists have manipulated and inflamed. The economic impact is in the tens of billions of dollars.

Governance in many of these afflicted regions is breaking down, turning swathes of land into vast zones of lawlessness.

The clashes have occurred on West Africa’s historic Muslim-Christian faultline.

Yet the conflict goes beyond religion, bringing into focus issues that are crucially relevant for the wider world.

They include the roles of population growth and climate change in fuelling disputes over land use, and the part that colonial-legacy divisions play in stoking violence.

The crisis has also turned a sudden, stark spotlight on Fulanis and their gruelling but timeless way of living.

Today, despite their millennia of history, the Fulani people find themselves assailed by stigma, political pressures and a shifting economy, their traditions so often out of kilter with the demands of modern societies.

Many Fulani, struggling to adapt, say their people have no choice but to fight to survive — or otherwise fade away.

In a special investigation, AFP sent a team of reporters across Nigeria.

In these exceptional reports, we explore the Fulani’s complex social and economic world, and we raise the question: Is this timeless people doomed to a bleak future?

Our first batch of stories, headed by Celia Lebur of AFP’s Lagos bureau, begins with a horizon-sweeping long read of the Fulani, their struggle to survive in the scorched lands of West Africa and the feud with farmers that is now escalating swiftly and bloodily.

From this panorama, we look in detail at the forces of history driving today’s conflict and the surging demand for beef that offers risks as well as rewards for pastoralists.

And we profile Mohammed Abubakar Bambado — a Fulani business tycoon who also happens to be a king.

——————————————————-

The long read : Nigeria’s War of the Land

“Move! Move!” The herders cry, the packed crowd divides, and a vast column of cattle charges through the swirling dust, their long sharp horns swaying like a forest. Hundreds, possibly thousands, of beasts push their way forward, trampling the ground strewn with plastic bags. It is mid-morning but already the heat is blistering. The buyers have arrived, and the hard bargaining can begin.

The scene is Agege market in Lagos — the largest livestock trading hub in West Africa. Here, each day, 50 truckloads of livestock are disgorged into its maw to supply the 20 million inhabitants of Africa’s biggest city. Nigeria has nearly 200 million mouths to feed, a figure expected to grow to almost 400 million by 2050.

Going hand-in-hand with this population boom is a vast, expanding market for meat and milk. And that demand, in turn, is having invisible, but wrenching, repercussions on Africa’s most populous country.

– The long trek –

Agege is, literally, terminus for the animals. They have been raised and fattened by nomadic Fulani herders many hundreds of kilometres away, sold at rural markets and ultimately brought to the mega-city. Some cattle, exhausted by the journey and weak from disease, collapse on arrival.

Lying on their sides, panting with protruding ribs, they seem like they are preparing to give up without a fight. These are not worth a great deal, their flanks too thin for much cash. But most, fattened up with grain and fodder, show a shiny coat and have the thick thighs of good health. All have come over vast distances: walking at first, then packed into large cattle trucks for the final leg to Lagos.

Today, their journey is almost over. Just a short walk away lie the city’s giant slaughterhouses. In a grubby car park, refrigerated vans are already waiting to load the meat. Aisha Maila is one of the few women in the organised chaos of the sprawling market. The elderly lady is marrying off her daughter in a few days and wants the celebrations to be something special. She is not rich, so she has come to buy the wedding dinner direct from the source. “How much for that big white bull there?” she asks, but the thousand dollar price-tag is too high.

“Too expensive,” Maila says, scouting out a more modest cow that she can afford. Maila’s shopping is small stuff. The big business is done between dealers and major butchers. Gambo Usman has found a potential buyer for his batch of fat-humped, long-horned cows, which have come all the way from neighbouring Chad.

“Yauwa, yauwa,” Usman says in the Hausa language of northern Nigeria, his phone clamped to his ear. “OK, good.” He explains the terms of the deal to his boss, a wealthy businessman in the northern Nigerian city of Kano. Usman is only the go-between. Twice a month, he crosses Nigeria by plane from north to south, travelling nearly a thousand kilometres (600 miles) between Kano and Lagos to sell the animals sent down south.

“The demand is getting bigger, and we sometimes have trouble meeting it,” said Usman, dressed in ripped jeans and muddy boots.

“There are shortages because of violence with farmers. Many herds have been decimated up there.”

“Up there” is Nigeria’s north. The majority of animals coming to the big cities of the south come from the borderlands of Niger, Chad and Cameroon.

– Cattle and conflict –

There, in the dry lands of the Sahel, the ancient way of life of herding is practised by the Fulani, a predominantly Muslim people with long traditions of nomadism. But the lifestyle is under pressure as never before. Big herds and big money are at stake: around 120 million cattle, sheep and goats.

Every November, when the dry season begins, the farmers and their animals move south searching for fresh pastures, to where the Niger and Benue rivers water the fertile plains in central Nigeria.

Once, there used to be room for everyone in the “Middle Belt”, the zone where a Muslim-dominated north rubs alongside a largely Christian south. Each complemented the other: milk was traded for corn, leftover hay from harvests fed the livestock, and dung from cows fertilised the soil.

Tensions could arise, especially when a herd ate or trampled a farmer’s field of crops — but traditional chiefs still had the power to keep the peace between rivals. Times have changed. In the north, the tough droughts seem to have been growing ever harder, while the brutal insurgency of Boko Haram has forced tens of thousands of people to flee the lands around Lake Chad.

Meanwhile, parasites that once plagued livestock have declined, opening up the land for cattle. So the Fulani people are shifting south — often, if they can, for good. With the dizzying speed of population growth in Nigeria in the late 20th century, land has become the subject of fierce competition.

With the dizzying speed of population growth in Nigeria in the late 20th century, land has become the subject of fierce competition. Step by step, conflicts over crops, water and livestock have grown.

The village of Angwan Aku, in the centre of Nigeria’s north, is now at the heart of a war in which more people have died than in battles against Boko Haram. The village, once home to settled farmers, a Christian community of the Adara people, was left in ruins in April. Monica Gabriel, lying on an old mattress on the floor of a nearby clinic covered in a thin red sheet, is a survivor.

A week after the killings, the 48-year-old farmer is still in shock, staring silently into space, the bullets that smashed into both her legs remain stuck inside. Her shaved head is crossed by a long scar. On her left wrist, a homemade bandage covers where the assailants hacked her with machetes.

Two nurses wave off the flies which come to feast on the wounds. Were it not for a small cough that moves her chest, an observer might think she was already dead.

– Massacres –

It was just after dawn and Gabriel had been cooking millet porridge for breakfast when a crackle of automatic rifles rang out in Angwan Aku.

“Someone shouted a warning, but we didn’t hear,” said her husband Dauda, his voice trembling as he recalled the moment.

“My mother was killed on the doorstep. My wife tried to run away — but they caught her.” He has not left his wife’s bedside since.

“We do not know why they attacked us,” he said. “We didn’t do anything to them.”

The gunmen went from house to house, shooting or hacking to death anyone they encountered — men and women, old and young.

In less than two hours, in this village of some 2,000 people, 27 were slaughtered and 16 seriously wounded.

Survivors claim that the attackers were “Fulani”: they say gunmen spoke the Fulani language and had lighter skin and high cheekbones, the stereotyped look of their group. But beyond that, there is no consensus.

Where did they come from, and what was their motive? Was it robbery? Were they another gang of bandits, in a country with so many already?

Or was it for revenge? Some blame a court decision on a land dispute, that ruled in favour of the villagers. Others claimed it was an argument over a woman.

As is so often the case, no one knows the truth, for there are as many stories as there are people in these tough lands.

The only certainty is that the terrible spiral of violence in Nigeria’s Middle Belt has been given another twist. In the past five years, the conflict has claimed at least 7,000 lives, and the economic cost is running at $13 billion (11.57 billion euros) annually, according to the NGO Mercy Corps.

Settled farmers, mainly Christian but hailing from several different ethnic groups, boast of ancestral ties to the land, buttressing their claim to own it. But such claims have been indirectly encouraged by an official policy: the government is throwing its support behind agriculture to diversify Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy.

– Torched homes –

Month after month of violence has turned swathes of the rural Middle Belt into a wasteland.

You can drive down long dirt tracks for hours, snaking through scenes of devastation, from burned villages of the Adara ethnic group to hamlets abandoned by the Fulani. In some places, smoke rises from the ruins of houses torched a few days earlier. Flames have reduced motorbikes to skeletons. Piles of corrugated sheets are all that remain of collapsed roofs. Only the yowls of frightened dogs break the silence.

The dead are speedily buried without a coffin and with the briefest of funerals — laid together in mass graves hastily dug by villagers before scavengers come to rip at their remains. At the village of Dogon Noma, where 71 people were killed and around 250 houses burned in March, each grave was dug to hold 10 bodies. The lines looked like a freshly ploughed field. The aftermath of these attacks is invariably a grim ritual, and one that inevitably drips more poison into this conflict.

Police typically arrive days after the attack. Their investigations lead nowhere. In the absence of justice, frustration metastasises into hatred. So those who call for peace face a challenge.

On a Sunday morning, preacher Yohanna Buru arrives at the evangelist church in the one-horse town of Mararaban. The crowds, those forced from their homes from the fighting, have come to communion for the sacrament and bags of food aid that go with it.

“Trust the Lord, only He can save you,” the pastor tells the congregation, wearing big black sunglasses and jeans.

“Do not seek revenge, but pray for your enemies and the salvation of their souls.” There are murmurs of surprise among those at prayer: this is not the usual vengeful rhetoric of their chiefs and political leaders, whose speeches of anger divide people by ethnicity and religion.

Skeptics say that leaders find casting blame on scapegoats easier than talking about poverty, crippling hunger and unemployment — especially in an election year, like 2019. Buru the preacher insists: “Fulani are not terrorists”.

In his home in Kaduna — where Islamic Sharia is the law — he invites Muslim preachers to celebrate Christmas and Easter alongside him, and repeats to anyone who wants to hear: “Dialogue is the only way out.”

His voice has became famous in this region, broadcast every Sunday on his own local radio show.

“I am a peacemaker,” Buru says. “But I know that not everyone likes it. I have received threats, intimidation… I am asked why I speak with the enemies of Christians.” He sighs. “It’s understandable,” he says after a while. “The land is their only wealth, all they have is to farm it. If we take that away, they have nothing left.”

– Cycle of revenge –

Oyama Kwanaki is one of those who has already lost everything. Lying on a hospital bed with a bullet wound, he is a tough man with staring eyes. They flash with anger.

“What I saw that night, I will never forget,” Kwanaki said. “If my path crosses with that of a Fulani, he will pay. I am not able to forgive.”

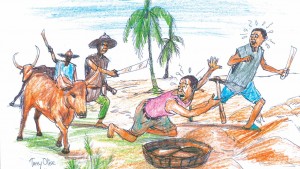

Revenge is taken communally, not against the men directly responsible. So now the countryside is full of young men, organised into militia gangs, armed with homemade rifles or bows and arrows, to defend their villages.

“They have AK-47s,” Kwanaki said. “You have to defend yourself.”

The Fulani have come here for countless generations. But because they moved with their animals, they were never seen as settling — and all are often considered “invaders”. Some 30 to 40 million Fulani people are spread over 15 countries, from the West African coastal state of Senegal to the Central African Republic in the heart of the continent.

Lines on the map of national borders mean little to them; the preservation of the herds are what their lives depend on. The fact that they have suffered from the violence just as much is largely ignored: such as in February, when 130 of them were massacred in southern Kaduna state in one night alone. Blamed and then attacked for crimes committed by others, the Fulani families gathered their animals, packed up one after the other, and set off on their way.

– Island of calm –

At the end of a long track, across bridges half collapsed, a village of round homes of mud walls stands. Here, in the Kachia grazing reserve in Kaduna state, the Fulani live — for the most part — on their own. The region has been hard hit by the conflict between farmers and herders, but Kachia, earmarked for nomads, is a refuge.

Some 18,000 people lived here four years ago, according to the latest estimates. But since then people have arrived in droves, fleeing the violence elsewhere. “There was nothing here when we got there, just the bush,” said Idriss Jamo, the only doctor for far around. “Nobody lands here by choice.”

Jamo is the exception; he came here a few years ago from Kaduna to open his basic clinic. The clinic has shortages of equipment and drugs, but the patients now at least have one doctor.

“We could have stayed in town, with all the modern comforts,” said Bilkisu, Jamo’s oldest daughter, her hair neatly tucked under a brown headscarf. “But my father got tired of seeing people die of malaria, and pregnant women lose their child before reaching the hospital,” said 24-year-old Bilkisu, studying microbiology at university in town. Life is quiet here.

The two mosques call the faithful to prayer five times day, marking out time for the people. There is also the market and the football pitch, which comes alive when the baking heat drops at dusk.

Phones are quiet: the network doesn’t reach here. There is no internet access, no state electricity. If you want power for your mobile, you pay a small fee to charge your device at a store with a little generator.

Isa Ibrahim is a herder -– half of the time. Otherwise he drives a motorbike, a taxi driver on two-wheels for hire, offering the escape out of the village the young men aspire to.

Ibrahim, 30, with a beard and his forehead tattooed with stars in the tradition of the Fulani, leaves his wife and children to zoom off for the half-hour trip on the rough tracks to the trading centre on a crossroads. People simply call it the “Crossing.”

There, among the tin-hut shops with phone network, he can finally call friends, listen to music and –- most importantly –- play pool, the main attraction.

Ibrahim was born in the area nearby, in a small village called Madakyia, at a time when life still revolved around the herd. Life was for father as it was for son.

The number of cows you counted in the herd was the measure of the man; it was who you were, your wealth, and your social status.

As a boy, he moved with the herds according to the rains in search of grazing, travelling with the animals, before returning to the village. They no longer lived quite as their ancestors had been; only a tenth of pastoralists now remain fully nomadic. But he had time to experience a life of camp and bushfires. It was a happy existence.

Then, in 2011, everything shattered. The post-election violence that followed the presidential election soon divided the Kaduna region along the religious and ethnic lines of its many different peoples. Christians against Muslims, Fulani against Atyap, Fulani against Ninzom, Fulani against Kaninkom… The villages burned one after the other. Eighty members of Ibrahim’s clan were slaughtered in one night alone. Of their hundred cows, two-thirds were slaughtered. The sheep were stolen.

So Ibrahim’s father and his wives, with 15 children, took refuge like so many others on the reserve. “The change was difficult,” said Ibrahim. “We started to farm the land because we had lost a lot of animals, so we could not count on that to live on anymore.”

– ‘The cow is magic’ –

Ibrahim wakes at dawn to milk the animals he has left before heading to look for work on his motorbike taxi. The cows’ milk is declining drop by drop and today there is not enough for the family, let alone to sell at market. Squatting beside a cow, Ibrahim’s 12-year-old brother pushes away a young calf wanting milk from its mother.

In the end, both clinging to the udders, the calf and boy both suck at the rich milk. The herds are precious. Only when a family member gets sick, or to celebrate a wedding or a birth, does the family sell a cow. The herd is the family’s bank, a savings account to be drawn on only in dire need.

“The cow is magic, more magical than the fairies!” wrote Fulani writer Tierno Monenembo.

“She feeds, she protects, she guides… She opens the doors of destiny.” But times are tough, and Ibrahim hankers for the old days.

“The flock is no longer a symbol of wealth, but of survival,” he said sadly.

“It has become impossible to go 10 kilometres in the bush without crossing a field, which is when we have problems with the farmers.

“The grazing routes no longer exist. Everything is cultivated.”

Nigeria, on the advice of the World Bank, set down plans as early as 1964 to protect 10 percent of the country for grazing lands for livestock herders. But the promises of the Grazing Reserve Act were largely ignored. Only a fraction of the reserves ever emerged.

Of the 415 reserves planned, about a hundred were gazetted, meaning that their creation was officialised, although only 20 are actually up and running.

But as the conflict spreads, the calls grow louder for the law to be implemented in the hope that the herders will settle for good — and that the violence ends.

The Kachia Grazing Reserve, where Ibrahim lives, is supposed to be a model example.

– Kalashnikovs and codeine –

For Ibrahim, it is now too dangerous to leave the reserve. “With the theft of cattle, bandits and criminals are everywhere,” he said.

“We never go far with the animals. We are poor, but here at least we are safe, and our children are going to school.” He himself did not have that chance. He wanted to be a vet, looking after the animals of his people -– but violence and poverty meant he never got the chance.

In Kachia, there are 21 primary schools and one secondary school – for nearly 6,000 students.

All are “nomadic schools”, set up over two decades ago to provide access for herders to give their children education. But the bitter fact remains: Out of the 10-15 million cattle herders in Nigeria, more than three million children do not go to school.

Even in Kachia, the “model” reserve of the Fulani, dreams of a glittering future crash and burn inside the decrepit walls of schools. More than 120 children squeeze into a classroom, many without desks, benches or notebooks.

Yusuf Abubakar is 16 years old — but in second year at school. He struggles to speak English fluently. Yet he still dreams of one day becoming governor, to “do what others have not done… to bring peace to the people, build schools and hospitals.”

In the oldest school, established in 1990, there are four teachers for 860 pupils. Lessons fall back onto learning by rote; students recite — without fault and in song — the capitals of the 36 states of the country.

“More than 90 percent of Kachia’s youth are unemployed — they sit in the village,” said 29-year-old teacher Shitu Abdullahi. “Some smoke cannabis or drink codeine.” The cough syrup of codeine, an opiate used to treat pain, numbs reality.

“They do not want to take care of livestock anymore, but they do not have a diploma, no qualifications,” said Abullahi. “How do you want them to cope?”

– Curse of crime –

The statistics are sketchy, but everyone will say it: the crime rate among Fulani youth has exploded in northern Nigeria. In the troubled state of Zamfara, large-scale cattle thefts and kidnappings for ransom have become the norm.

“Many of those who lost everything in attacks have gone to get weapons to defend themselves, and also started to get involved in kidnappings and cattle rustling,” said Malam Mansur Isah Buhari, a university lecturer in Sokoto.

An AK-47 Kalashnikov assault rifle costs around $100. Within the gang structure, the Fulani are minions, although there is a lot of money at stake for leaders. The spiral of violence is endless. No one is spared.

“Criminals act indiscriminately, the Fulani attack Fulani, who seek in turn a way to survive,” Isah Buhari said.

The stolen animals are loaded alive on trucks, untraceable in the vast marketplace of the livestock economy. There are eager buyers and the animals pass from dealer to dealer. Money changes hands, until, eventually, the animals join that gruelling forced march to Lagos, and their rendezvous with the slaughterhouse

——————————————————-

Hunger for beef offers rewards and risks for Nigeria’s pastoralists

With over 200 million people and an emerging middle class, Nigeria is witnessing a boom in demand for meat that offers potential but also risks for the semi-nomadic herders who provide most of its beef.

According to government estimates, Nigeria, consumes 360,000 tonnes of beef each year, accounting for half of all West Africa.

In per-capita terms, consumption is low compared with advanced economies, but it is growing fast, and expected to quadruple by 2050.

Today, most of the demand is met by pastoralists from the ethnic Fulani group, who follow time-honoured techniques of raising cattle, driving them south to pastures and taking them to market.

During the dry season, the herders come down from the arid Sahel to the fertile plains of central and southern Nigeria, seeking water and pasture for their livestock.

– Tensions –

The millennia-old activity has been thrust into the spotlight in recent years because of worsening confrontations with sedentary farmers over access to land and water.

Clashes have claimed 7,000 lives over the past five years and cost the Nigerian economy $13 billion (11.57 billion euros) annually, according to a report in May by the NGO Mercy Corps.

The friction has roots dating back more than a century. Droughts, population growth, the expansion of sedentary farming into communal areas but also poor governance have all played a role.

Such neglect has pastoralists feeling isolated, according to Ibrahim Abdullahi, secretary of Gafdan, a national union of herders.

“Nothing was done to implement the grazing reserves designed by the law in the 1960s — most of the land has been sold and is now cultivated by farmers who grow crops,” he said.

Nomadic herders also find themselves far from the channels of the meat trade, while many markets and outdoor slaughterhouses lack basic sanitary conditions, such as running water, animal shelters and cold storage rooms, he said.

“At all the levels of government, the livestock sector was always marginalised in favour of agriculture. Some states still allocate less than two percent of their budget to livestock,” he added.

– Opportunity –

As Nigerians clamour for meat, can this ancient practice — with its long supply chains, climate risks and social tensions — compete against sedentary farming, which has high productivity and lower risks?

Jimmy Smith, director of the Institute for International Research on Livestock Farming (ILRI), based in Nairobi, argues that the system can not only survive but also flourish — in the right conditions.

“Pastoralism has been established for millennia — in the past we’ve seen it’s a very efficient system if you look at the input/output relationship. Very little is invested, but a reasonable amount is harvested,” he told AFP.

This model can prosper if the right support is put in place, he said.

“For example, it is possible to grow more forage and grain in sub-humid zones to create and develop feed markets for livestock based in northern areas, where it’s dry.”

“One animal which can give two litres (3.6 pints) of milk today could give 10 litres in the future.”

The government is mulling several plans to boost cattle raising and ease tensions over access to land.

They include initiatives for the creation of “cattle colonies” — dedicated areas where pastoralists can graze their animals and have access to veterinary and other care.

But these schemes are expensive and have already drawn flak from Nigerian states, which oppose handing over land for this use.

Another idea, for encouraging ranching, is doubted by agricultural experts. They point to a long list of past failures, during the French and British colonial period, to set up high-productivity “modern farms” in West Africa.

– Imports –

Nigeria has considerable livestock — nearly 20 million cattle, 40 million sheep and 60 million goats — but about 30 percent of slaughtered animals are purchased from abroad, mainly from neighbouring Cameroon, Chad, Mali and Niger.

Often the herds are driven for hundreds of kilometres (miles) to be sold at border markets like Illela, a trading post between Niger and Nigeria.

The animals are then trucked to the cities, where they are sold again, slaughtered and butchered.

“As it is now, there’s no way Nigeria can produce all the meat and the milk it needs for its growing population,” said Smith.

“A significant proportion of animal source food demand will most likely continue to be met by importation.”

Nigeria’s hunger for meat is likely to be replicated across Africa, if expectations of population and income rise hold true.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates the continent will experience a doubling in consumption of beef, pork and chicken between 2015 and 2050.

With most of the meat consumed in Africa still coming from pastoralism, Smith said, “All we need is to modernise it.”

——————————————————-

History : Forces of history drive Nigeria’s herder-farmer conflict

Beneath an escalating conflict between herders and farmers in central Nigeria lies a relentless but often under-reported force: history.

Events in the 19th century helped shape today’s violence between mainly Muslim Fulani cattlemen and largely Christian farmers — a battle of blood and identity.

Sokoto, an ancient city in northern Nigeria, is where many Fulani, a semi-nomadic people stretching from Lake Chad to the Atlantic coast, have their spiritual roots.

Cross-legged, his eyes closed and palms turned upwards to the heavens, Saidu Bello prays before a huge marble tomb covered in blue velvet: the resting place of Usman Dan Fodio, revered by many as a Muslim saint.

“I pray Allah to give me the same strength as he gave to the Shehu,” says Bello, a 29-year-old trader, referring to Fodio.

“Whenever I have doubts, I come here for his help to make the right decision.”

– Caliphate –

In 1804, Fodio, a learned Fulani, declared holy war on despotic leaders.

Urging Muslims to observe a “pure Islam,” he launched an insurrection that, four years later, led to the establishment of the caliphate of Sokoto.

The state was as large as it was prosperous, extending from modern-day Burkina Faso to Cameroon — an area that took four months to cross end-to-end. The caliphate ended when its last leader was killed by the British in 1903.

“Usman Dan Fodio united former Hausa kingdoms and brought peace to the whole region,” says Sambo Wali Junaidu, advisor to the current sultan of Sokoto, a direct descendant of the first caliph and Nigeria’s highest-ranking Muslim.

“He fought social injustices and undue privileges.”

Fodio’s charisma and writings — treatises and poems written in Arabic, Hausa and the Fula language — inspired Fulani jihads in West Africa throughout the 19th century.

And his popularity persists today. At the shrine in Sokoto, pilgrims come from as far as Senegal, laden with offerings.

Many of these faithful are barely-literate Fulani herders who have not read any of Fodio’s writings but learned of him through madrassas, or Islamic schools.

– Roots of conflict –

The conflict in Nigeria between Fulani and sedentary farmers has erupted in a fertile central region called the Middle Belt.

Demand for water and access to land, driven in part by a surging population in a country of 200 million, are among the contemporary causes for the fighting.

But there is a deeper reason: the Middle Belt lies in Nigeria’s religious faultline, between the predominantly Muslim north and mainly Christian south. It is also a region that, historically, suffered chronic unrest.

Lying on the southern rim of the caliphate of Sokoto, the Middle Belt was largely populated by animist communities. These were frequently raided by the caliph’s troops to provide slave labour for the plantations, salt mines or burgeoning iron industry which made the empire so prosperous.

Contemporary descriptions by traders are eye-opening. In 1824, in the great commercial hub of Kano, the ratio of the population was 30 slaves to every one free man.

“Native populations, living in this zone of influence during the time of pre-colonial Islamic empires, were psychologically scarred” by the raids and the enslavement, says Alioune Ndiaye, a specialist on Nigeria at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec, Canada. Many became Christian as a result, and the traumatic episode resonates in Nigeria today, he says.

“There is still this dread among people in the south that the northerners are coming ‘to dip the Koran in the ocean,’ as the saying goes,” Ndiaye says.

– ‘Blame the Fulani’ –

This backwash of fear and mistrust is often reflected in the Nigerian media, whose main outlets are owned by a southern tycoon. Fulani herders are routinely called “terrorists,” and a supposed Fulani “plot” to Islamise Nigeria, begun under Fodio, is also media fodder.

Stigmatisation worsened after the election in 2015 of President Muhammadu Buhari, a Muslim Fulani from the north. His every decision — from the speed with which he has condemned massacres to the response of the armed forces and the appointments he makes in the army and police — is scrutinised through the lens of ethnic bias, says Ndiaye.

Ibrahim Abdullahi, who represents an association of herders in the northern city of Kaduna, says the notion of a modern-day “Fulani jihad” is a “pure fantasy” that was being manipulated for political ends.

Unlike Mali and Burkina, where jihadist groups exploit ethnic resentment to recruit among Fulani people, the Fulani in Nigeria generally have no claims based on religious ideology.

“Most of the Fulani pastoralists are poor and haven’t been to school. They don’t have a voice, there’s no organisation or political elite speaking on behalf of all of them,” he said.

“That’s why each time something goes wrong in Nigeria, people blame the Fulani.”

——————————————————-

Profile : In the heart of the metropolis, a king of Nigeria’s herder Fulani

The Sarkin Fulani of Lagos sinks into his white upholstered throne, lays a hand on the sculpted golden cow head that forms the armrest and scans the subjects gathered at his feet.

Mohammed Abubakar Bambado is a busy 49-year-old businessman with a successful port handling firm in Nigeria’s economic metropolis. He is also a king.

The Sarkin Fulani of Lagos is one of Nigeria’s most influential members of a mainly Muslim community of nomadic herders from the far north, at a time when relations with the country’s largely Christian farmers are deteriorating.

All of those waiting for an audience to air their problems in Bambado’s cramped assembly room are ethnic Fulani-Hausa, two closely-tied northern ethnic groups. But few of them know the herding life.

Fulani-Hausa now make up around a quarter of the population of Lagos — around five to seven million people — in the ethnically Yoruba-dominated south of Nigeria.

The congregation is overwhelmingly urban — district chiefs kneel alongside the representatives from the ranks of the “okada” motorcycle taxis and the beggars who wander between the racing traffic in downtown Lagos.

“I am here to solve their problems,” said Bambado, a thick-set man with a Mercedes 4×4 who himself does not fit the stereotype of the weather-beaten wanderer.

Their problems are centred on the push and hustle of life in Nigeria’s frenetic economic capital. A money-changer was kidnapped and murdered. His family does not trust the police, and begs the influential chief to follow up on the investigation. He says he will.

There are land disputes, family quarrels, beatings and armed robberies, all brought to the chief for advice and help. He has no official powers, but when he speaks, the police and politicians listen.

“He is a good man. When something serious happens, even if he is travelling overseas he always picks up his phone. And if it is necessary, he flies back to Nigeria,” says Suleiman Ibrahim, a trader who has come to Bambado to adjudicate a family feud.

Indeed, the time Bambado spends on his gilded throne in his somewhat ramshackle palace in Surulere, the popular residential district of Lagos where he lives, is just part of his busy schedule.

The married father-of-three often travels for work and spends around half the year in London and Dubai on business.

– Blood and belief –

The Fulani seem to be a people without borders — the wider community is estimated at between 30 million to 40 million scattered across fifteen countries from Senegal to the Central African Republic. In the north, every city has a Sarkin Fulani or a Sarkin Hausa.

Officially, Bambado’s authority extends only to the borders of Lagos, but his influence spreads wider and he is a powerful player in Nigeria’s political mosaic. That position has become increasingly important in recent years as conflicts between Fulani and sedentary farmers have swept Nigeria’s fertile central region.

The bloodshed has been stoked by demand for water and access to land, driven in part by a surging population in a country of 200 million. The Fulani have also been accused of “terrorism” and aggression.

“Anywhere you see a Fulani man, people see them as killers,” said Bambado.

“But it is not true. A Fulani man is a wonderful person, he accommodates, he likes his people, he likes his neighbours, he interacts, he is a very social person. But you know what? There is no society that has no bad eggs.”

– Drawn to Lagos –

Bambado’s grandparents were from an educated, religious family and were among the first migrants to leave the arid northern state of Jigawa and travel south at the beginning of the 20th century.

They eventually settled on the Atlantic coast and his grandfather, a trader in kola nuts and gold nuggets, increasingly became a linchpin of the Fulani community.

“When people from the north stayed in Lagos, he was the one to welcome them. They became more numerous. So one day, they decided that they needed a leader: my grandfather,” said Bambado, who inherited the title when his father died in 1994.

The first Sarkin Fulani of Lagos balanced his royal duties with diversifying his business interests, investing in the cattle trade and the docks.

He set up a port handling business, using “brothers” as labour, which has passed from father to son — like the Sarkin title — for three generations.

Bambado has continued in this tradition and Dockworth Services International now employs 1,500 people. He is also a central figure in the meat market in Lagos, which is the key sales hub for the cattle reared across the north and centre of the country. He even keeps a herd of around 300 cattle on the outskirts of the city to keep him tethered to his heritage.

And despite his travel schedule and the wide dispersal of his community across multiple countries, he remains loyal to his birthplace. “I am a Lagosian first and foremost,” he said.