10 April 2020. BBC: Police have been told to be “consistent” when applying measures introduced to stop the spread of coronavirus.

It follows criticism that some forces have gone too far when trying to ensure people follow the rules.

What powers do police have?

Police have wide-ranging powers to help fight coronavirus, by enforcing social distancing measures designed to keep people apart.

The three key tools they have been given are:

- The power to detain someone to be tested if they are believed to be infectious

- The power to close a wide range of non-essential businesses

- The power to restrict your right to move around and be part of a gathering

But there is an enormous gap between what the government would like people to do and the actual limits of the law restricting movements. The restrictions came into force as a “statutory instrument”, which means it was created by ministers, in each part of the UK, with no debate or vote before it became law.

The rules are broadly the same across the UK, but each country has its own regulations.

Individual police officers have enormous discretion and there will be differences in what they decide to do. That has led to accusations that some are being overzealous.

What punishments can police enforce?

A police officer can order a non-essential business to close while coronavirus regulations are in place.

Police can also enforce the two key social distancing rules, which ban:

- Leaving the place where you live “without reasonable excuse”

- Being in a public gathering of more than two people

If someone refuses to follow the regulations – for instance a request to go home – officers can give them an on-the-spot fine of £60, reduced to £30 if paid within 14 days. If they keep breaking the law, more fines can be given – up to a maximum of £960.

Police could ultimately charge someone with the more serious criminal offence of breaching coronavirus regulations and a direction to follow them. This could lead to a conviction in a magistrates court and an unlimited fine.

What is a reasonable excuse to leave home?

A “reasonable excuse” which would avoid a fine includes:

- Going shopping for “basic necessities” (food, medicine and items essential for the home). There’s no definition of what counts as “basic necessities” (more on this below)

- Exercise, including with members of the same household

- Travelling to and from work, if “absolutely necessary”

Police can’t order you home if you’re out helping someone else with their care, off to the doctor, or carrying out another public service.

It is important to note that it is not a crime to leave your home to flee harm – for example, domestic abuse.

How is this different to what the government wants?

This is where the problems start.

There could be “reasonable excuses” that the government has not thought of.

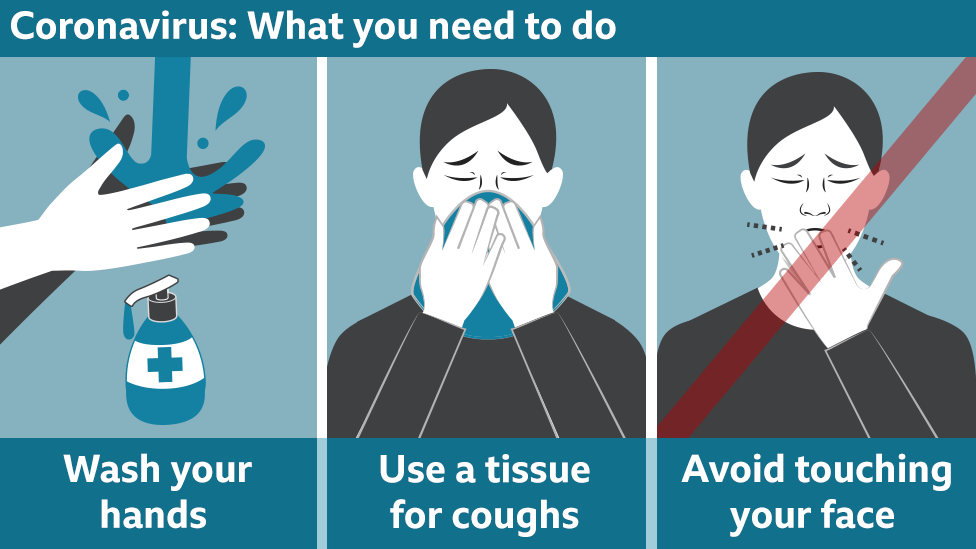

And the government’s instructions to the public for preventing the spread of coronavirus go far further than the laws police have to enforce them.

Take exercise. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said: “People will only be allowed to leave their home for… one form of exercise a day”.

That sounded like a clear legal order – and the science behind it may be very clear, particularly in crowded cities.

But that’s not the law. There is no legal ban on exercising more than once a day in England, Scotland or Northern Ireland. However, in Wales, which sets its own health regulations, exercising more than once a day is now illegal – and potentially a criminal offence.

What about travelling to exercise? The College of Policing has now told officers in official guidance: “Use your judgement and common sense. For example, people will want to exercise locally and may need to travel to do so, we don’t want the public sanctioned for travelling a reasonable distance to exercise.”

What’s a reasonable distance? That’s not defined for the officers who are now expected to enforce it.

The law may also prove vague in relation to some jobs as it puts the decision in the hands of an officer as to whether the work someone is out and about doing could be conducted from home.

It has left many people confused, with Nottingham Police revealing its switchboard was jammed by callers asking for advice.

Have police misused the powers?

As the Easter weekend approached, the Northamptonshire force suggested it might start policing supermarkets, if people didn’t heed the official warnings, and checking “baskets and trolleys” to see whether people were buying “legitimate, necessary items”.

Cambridgeshire police tweeted that officers were pleased “the non-essential aisles were empty” at one supermarket.

Both forces have now admitted they have no right to snoop in people’s baskets.

Separately, Daniel Connell, of Rotherham, won an apology from South Yorkshire Police after an officer ordered him to leave his own front garden.

The law explicitly says people can all go about their private business at “the premises where they live together with any garden, yard, passage, stair, garage [or] outhouse”.

So the law recognises that if you’re on your own property, you are on private land and, as a consequence, you should be able to sensibly comply with the distancing measures.

Derbyshire Police took enormous flak in the first week of this quasi-lockdown after it followed Peak District walkers with a drone.

Former Supreme Court Justice Lord Sumption says the force went too far, but its chief constable says the drone operation was aimed to prevent the national park being over-run, increasing the likelihood of contagion.

Last week, people were told to go to “local” beauty spots, if they want to go walking, while observing social distancing. But the law doesn’t require walking to be “local” – nor does it ban you from driving to the countryside to go walking.

Cheshire Police says it has summonsed someone to court for going out for a drive because they were “bored”.

Is driving to relieve the boredom of being stuck inside a reasonable excuse?

We won’t know unless that’s tested in court by someone who challenges a fine.

While the Coronavirus law says nothing specifically about going for a drive, police do, of course, have a general power to stop vehicles and enter property.

So a constable can pull you over and ask why you’re out – and if you don’t have a “reasonable excuse”, you could be committing an offence.

That said, the official guidance to police forces doesn’t rule out road blocks if a force thinks they are necessary. It just warns that checking all vehicles would be “disproportionate”.

What are police now being asked to do?

Officers are now being told to follow the “Four Es”:

- Engage with people – ask them why they are out

- Explain the law and the need to be inside, stressing the risks to public health and the NHS

- Encourage them to go home if they have no reasonable excuse

- Enforce only as a last resort

The National Police Chiefs Council has urged people to use their common sense – by thinking about whether they should leave home. And it wants officers to exercise their discretion by focusing on the law’s aim and purpose.